Auteur: Jean-Michel Arnal, Responsable des soins intensifs, Hôpital Sainte Musse, Toulon, France

Date: 19.10.2018

Last change: 09.09.2020

FormattingUne étude physiologique récente a démontré que la pression œsophagienne fournit une estimation de la pression pleurale à mi-thorax à tous les niveaux de PEP. Par conséquent, une mesure absolue de la pression œsophagienne est utile pour le réglage de la PEP et le monitorage de la pression transpulmonaire.

Alors comment procéder pour mesurer correctement la pression œsophagienne ?

Le ballonnet œsophagien doit être positionné et gonflé correctement et il convient de vérifier ensuite son positionnement.

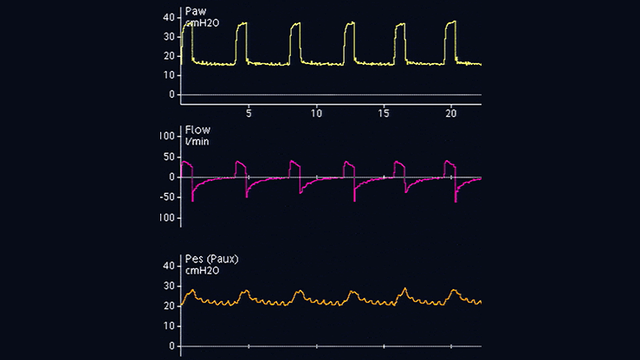

La position optimale du ballonnet œsophagien se situe au niveau du tiers inférieur de l'œsophage, à une distance de 35 à 45 cm des narines. Lorsqu'un patient est en position semi-couchée, le ballonnet vide est d'abord introduit dans l'estomac, qui se situe à environ 50 à 60 cm des narines. Le ballonnet est ensuite gonflé à un volume standard (1 ml pour un cathéter Cooper Surgical et 4 ml pour un cathéter Nutrivent). La pression gastrique affiche une déflexion positive au cours de l'inspiration chez les patients passifs et respirant spontanément. La position gastrique est confirmée par l'application manuelle d'une compression épigastrique, qui déclenche immédiatement une augmentation de la pression gastrique (voir figure 1).

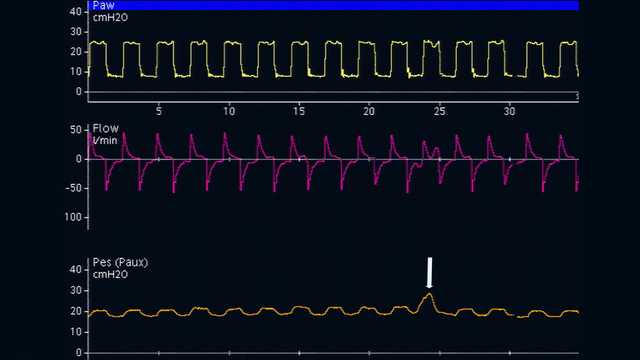

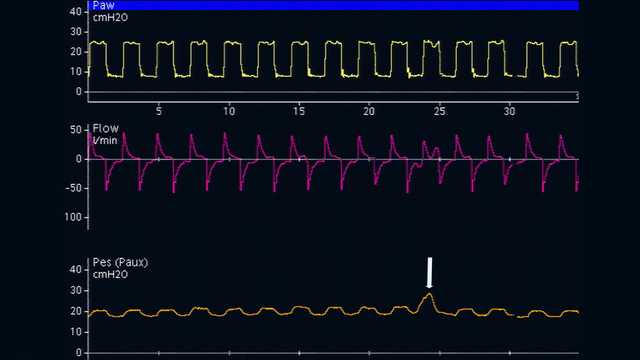

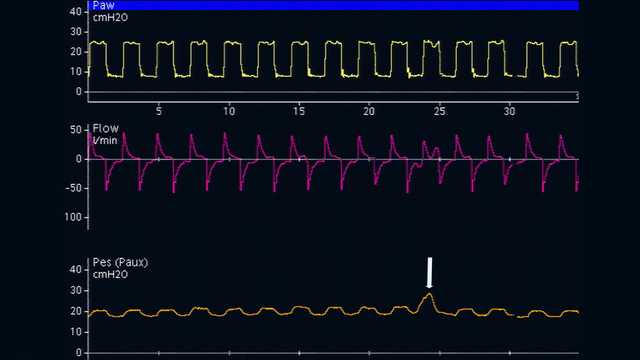

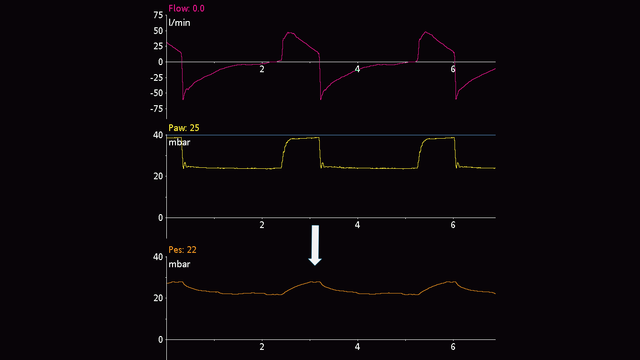

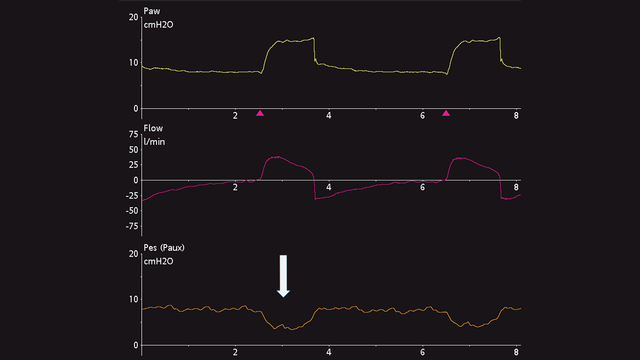

Le cathéter œsophagien est ensuite doucement retiré alors que le ballonnet est toujours gonflé, afin de positionner le ballonnet dans le tiers inférieur de l'œsophage. Lors du passage de la pression gastrique (voir figure 2) à la pression œsophagienne (voir figure 3), la ligne de référence de la forme d'ondes de pression change et des oscillations cardiaques apparaissent.

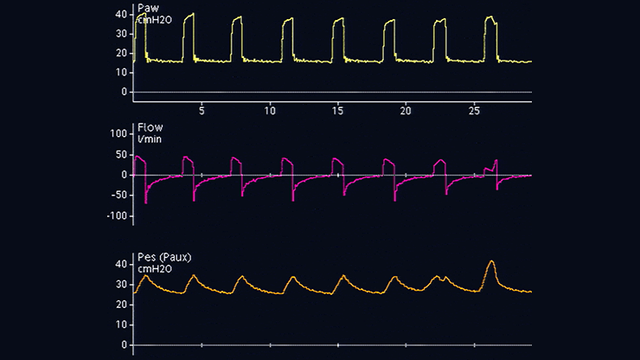

Les déflexions de pression œsophagienne sont positives pendant l'inspiration chez des patients passifs (voir figure 4), mais négatives chez des patients respirant spontanément (voir figure 5). Si des oscillations cardiaques perturbent le signal de pression œsophagienne, vous pouvez encore retirer le cathéter de 2 à 5 cm.

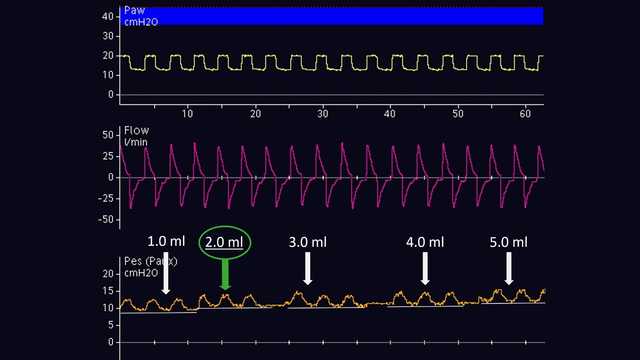

Le volume d'air pour un gonflage adéquat du ballonnet doit être titré individuellement. Cela n'est possible qu'avec des patients passifs. Conformément à la méthode proposée par Mojoli et al (2016), le gonflage du ballonnet s'effectue progressivement de 0,5 à 3 ml suivant un incrément de 0,5 ml pour un cathéter Cooper Surgical et de 1 à 8 ml suivant un incrément de 1 ml pour un cathéter Nutrivent (voir figure 6). Au cours du gonflage progressif du ballonnet, la ligne de référence de la pression œsophagienne augmente et l'amplitude de la déflexion de la pression œsophagienne varie. Le volume de gonflage adéquat est celui associé à la plus grande déflexion de la pression œsophagienne. Si deux volumes de gonflage différents affichent la même amplitude de déflexion de la pression œsophagienne, le volume de gonflage le plus faible est sélectionné.

Une fois le ballonnet positionné correctement dans l'œsophage et gonflé, la vérification est réalisée au moyen d'un test d'occlusion. Le principe consiste à fermer les voies aériennes en fin d'expiration pour en modifier la pression et à vérifier que la pression œsophagienne varie selon le même volume.

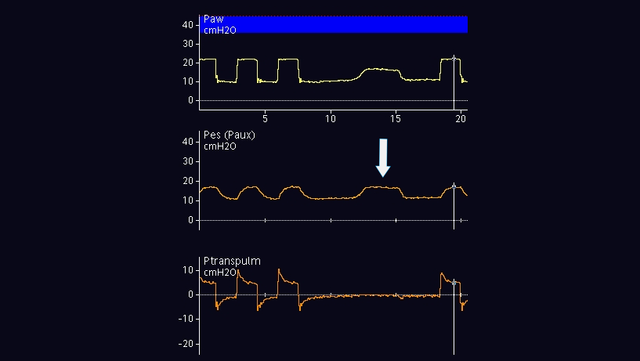

Chez des patients passifs, vous pouvez réaliser une occlusion de fin d'expiration. Lorsque la valve expiratoire est fermée, appliquez une compression manuelle externe sur la cage thoracique des deux côtés de la poitrine pour observer une déflexion positive des pressions des voies aériennes et œsophagienne. L'amplitude de l'augmentation des pressions des voies aériennes et œsophagienne doit être identique. En d'autres termes, la pression transpulmonaire ne doit pas changer (voir figure 7).

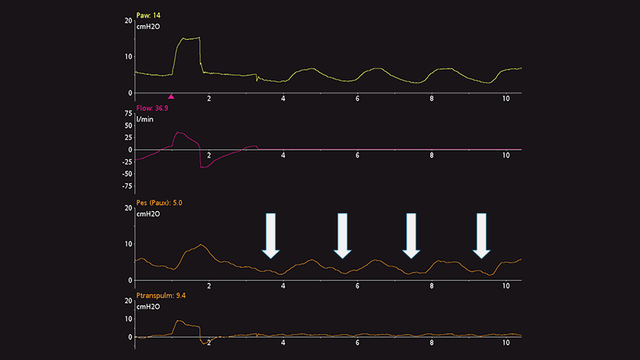

Chez des patients actifs, le test d'occlusion dynamique utilise également une occlusion de fin d'expiration. Il n'y a pas besoin d'appliquer une pression manuelle sur le thorax, car le patient délivrera un effort inspiratoire spontané pendant l'occlusion. Le résultat est une déflexion négative des pressions des voies aériennes et œsophagienne. L'amplitude de la diminution des pressions des voies aériennes et œsophagienne doit être identique, c.-à-d. que la pression transpulmonaire ne doit pas changer (voir figure 8).

Si vous souhaitez surveiller la pression œsophagienne en continu, il est important de réévaluer la bonne position et le volume de gonflage.

Citations complètes ci-dessous : (

Recommandations prouvées cliniquement pour utiliser correctement la pression œsophagienne chez les patients présentant un SDRA.